Last night, tho, was fascinating. David Zach, futurist regaled us with an entertaining and educational speech on the nature of progress and the importance of tradition. It was refreshing to hear somebody talk about the importance of holding on to tradition in a roomful of architects. I'm not pleased with the direction of modern architecture and its obsession to violate any and every ideal of form and function. I'd even go as far as to say that I'm disgusted with a lot of the crap [one example] people are building these days.

Maybe you can guess where this is going...

understand this if the building itself was pivotal in history, but the bank on Main Street probably wasn't, unless it happens to be the work of Louis Sullivan. An extension of the original design is not going to confuse history geeks. Then we have art museums... They used to display plaster casts and mock-ups of architectural styles, especially of the classical orders; you could visit a museum and actually learn about ancient art and architecture in its intended form. Now at the local art museum, we get fragments; pieces of sculptures, funeral goods in separate cases, the door of a citadel, all removed from their context. All you can appreciate is craftsmanship. I'd rather experience an intact Antinous as Bacchus, and know what it was like to walk thru that door now hanging lamely on the wall, without having to travel all over the world.

understand this if the building itself was pivotal in history, but the bank on Main Street probably wasn't, unless it happens to be the work of Louis Sullivan. An extension of the original design is not going to confuse history geeks. Then we have art museums... They used to display plaster casts and mock-ups of architectural styles, especially of the classical orders; you could visit a museum and actually learn about ancient art and architecture in its intended form. Now at the local art museum, we get fragments; pieces of sculptures, funeral goods in separate cases, the door of a citadel, all removed from their context. All you can appreciate is craftsmanship. I'd rather experience an intact Antinous as Bacchus, and know what it was like to walk thru that door now hanging lamely on the wall, without having to travel all over the world.An extension of mindless preservation is the modernists' attitude that it's not acceptable to design buildings in the classical idiom. The History of Architecture professor at the University of Kansas would never waste any opportunity to condemn the revivalism of the late 19th and early 20th centuries and then, in the very next breath, wax poetic about the renaissance. Hmmm... what's the frakking difference? Granted, the later revivals were often no more than shallow fads, but a great deal of revival architecture has its own merit--the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts comes to mind--and you just can't deny the charm of a small-town main street. I had a text book in my high school drafting that actually compared modern design to Victorian stereotypes. The rendering of the modern building was sleek and professional; the rendering of the Victorian building was a shoddy freehand sketch of a western false front. Propaganda at its basest, in a classroom where the teacher told us the Old Courthouse in downtown St. Louis was ugly and should be torn down. Buildings are products of their time and place, and should be judged accordingly.

I'm not saying that there should be a literal revival of classical architecture, but that we shouldn't throw away the lessons of Vitruvius just because they're old. A building isn't a great work of architecture just because an architect figured out a new way to twist steel or the engineer figured out how to extend a cantilever even farther. The Sidney Opera House is great architecture because it evokes the spirit of its site; the Bilbao museum is a novelty that has now been repeated ad nauseam. Fallingwater is great because it respects its site; the Sears Tower is just a skyscraper on steroids. The classical laws of proportion can be applied to contemporary design. We can respect our past and still look toward the future.

I'm not saying that there should be a literal revival of classical architecture, but that we shouldn't throw away the lessons of Vitruvius just because they're old. A building isn't a great work of architecture just because an architect figured out a new way to twist steel or the engineer figured out how to extend a cantilever even farther. The Sidney Opera House is great architecture because it evokes the spirit of its site; the Bilbao museum is a novelty that has now been repeated ad nauseam. Fallingwater is great because it respects its site; the Sears Tower is just a skyscraper on steroids. The classical laws of proportion can be applied to contemporary design. We can respect our past and still look toward the future.You might want to sit down for the sermon...

We'd be better as individuals and as a society if we would cherish our origins instead of stamping them into the dust in an effort to prove our individuality. Ultimately, any innovation will cease to be novel, and what is left if we eradicate the source of the innovation?

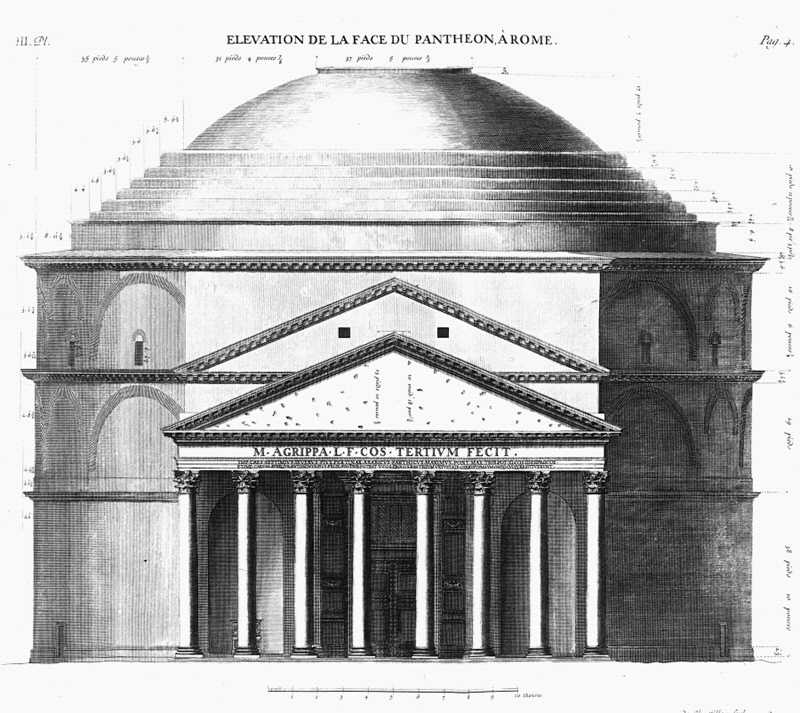

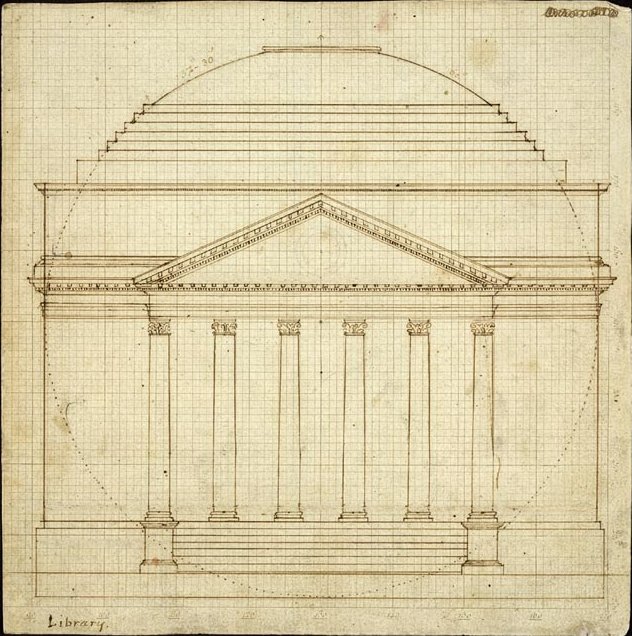

A comparison of the ancient Roman Pantheon, built by Hadrian, to the University of Virginia Rotunda, designed by Thomas Jefferson. Both of which academics consider great works of architecture. The Pantheon draws it fame from its structural system and awe-inspiring interior space; architectural historians praise the Rotunda for its harmonious exterior [follow the link for cool interior panoramas]. So... are revivals good or bad?

A comparison of the ancient Roman Pantheon, built by Hadrian, to the University of Virginia Rotunda, designed by Thomas Jefferson. Both of which academics consider great works of architecture. The Pantheon draws it fame from its structural system and awe-inspiring interior space; architectural historians praise the Rotunda for its harmonious exterior [follow the link for cool interior panoramas]. So... are revivals good or bad?

3 comments:

Then again, I loved the book In Ruins by Christopher Woodward. Ruins tell us many things, one of which is that we are mortal, civilization is difficult and I would assert that ruins can be beautiful. In one essay, CW explains that the colosseum after the fall of Rome supported all sorts of life, had microclimates and plants that existed nowhere else in Europe (brought in on the fur of animals that performed or died there) and was a source of inspiration for poets and lovers through the centuries.

After it was excavated, all of that inspiration was lost. It died only after it was supposedly brought back to life.

Thanks for linking and complimenting my talk.

hey! thanks for your comments. i agree with you inspite of my generalizations. so-called preservation often sterilizes the relics of our past.

that's really my beef; ruins-in-the-wild are beautiful, poignant, and fascinating; museum-ruins are usually none of the above.

so... do i get a book? hehehe

Post a Comment